The game of luck is also a game of skill

Luck plays a role in all outcomes, and it’s a worse sin to confuse luck as skill than the other way around.

Jan 2022: What luck is, and when it isn’t

Anoop wrote in this (if I may say so) stellar post about momentum that there’s a stark difference between luck and skill. That luck, indeed, is important in investment returns, but any fund manager’s outperformance over long periods of time is probably less a function of luck than skill. But the problem really is: how do you distinguish between luck and skill?

As Anoop writes, one way to tell whether, in a field, a performer is influenced by luck or skill, then the Michael Mauboussin book, The Success Equation, has a clue. If you can lose on purpose, then it’s going to be more about skill. If you can’t, then there’s luck involved. A tightrope walker has to have skill - it’s rather easy to lose on purpose (and rather painful, I imagine).

But in a card game where you pick a card and I pick one, and the bigger one wins: that is difficult to lose on purpose. That’s more about luck. Unless I play unfairly (marking the cards) I can’t lose (or win) on purpose. If I had a 10 game winning streak, I might start imagining it’s my skill indeed, because come on, who gets a 10 game streak? And just when I start to think so, I get another five game winning streak. At this point, other people are telling me it’s all me, it’s my skills. You know how this will end: badly, most of the time.

Confusing luck for skill is often disastrous. However, what appears to be purely luck, at first glance, can often be peppered with skill when you look deeper. Sure luck is involved, but it takes skill to convert that luck into a win.

For me to make this point I’m going to give you three examples, in increasing order of complexity.

Monty Hall Cars and Goats

In a show called “Let’s make a deal” in the US, a host named Monty Hall would show you three doors. Behind one is a car, and behind the other two are goats. If you select the door with the car behind it, you win the car. A goat gives you nothing.

You choose one, and instead of opening that door, Monty Hall opens one of the other doors revealing it has a goat inside. And then, gives you an option to switch your selection from what you originally chose, to the one remaining door. Should you switch?

At first glance it seems like it’s a game of chance. Of the remaining two, there’s a 50% chance that you’d selected a goat so switching, or not, should be a similar probability?

But when you look a little deeper, it strikes you that there’s a piece of information that changes the odds. Monty Hall will ALWAYS open a door with a goat. You started off with a 33% chance of picking the car. If you picked the car, switching was a bad idea.

But you had a 66% chance of having picked a goat initially. Given that the other goat-laden-door is now eliminated, you should switch.

Effectively, the probability you will win the car is 66% if you switch. This isn’t obvious - it takes a little more thinking, largely to work around the mental bias that if you have two choices, it’s a 50% probability. To understand this better, here’s a video that illustrates the solution.

(Note: 66% is only useful as a probability if you are allowed to play this game many many times. If you only get to play it once, the probability doesn’t get enough time to play out. More on this later)

Anil, Beena and Joseph

Mauboussin also explains the power of information in a video talk illustration

Anil is looking at Beena

Beena is looking at Joseph

Anil is unmarried

Joseph is married

The question: Is an unmarried person looking at a married person?

(Answers can be: A: Yes , B: No, or C: “Not enough information”).

The first thing that comes to mind is: We don’t know if Beena is married or not. So, C: “Not enough information”.

Looking more closely: Beena can be only in two states: Married or unmarried. (I will leave any other states like “it’s complicated” to Facebook territory)

If:

- Beena is married: Anil’s looking at her, and Anil is unmarried

- Beena is unmarried: Beena’s looking at Joseph and Joseph is married.

In both cases, an unmarried person is looking at a married person. The answer was A, but it took deeper digging.

Why am I going on with this? What you first see as pure chance may not be chance at all. Look a little more, and you have answers.

The Unfaithful Husband Problem

There’s a village in which there are only 40 married couples, and the custom is that every woman knows about any man who is unfaithful, but not her own husband. Another rule is that if a woman finds out her husband is unfaithful, she must shoot him that very night. They don’t discuss fidelity with each other, but they’re all very logical.

Now in this strange village, every man has been unfaithful. Queen Josephine, knowing this to be a problem, makes one statement to all the women: At least one of your husbands has been unfaithful.

What happens next?

The first thing that comes to mind is: Since every woman knows of 39 other unfaithful men, the queen’s statement is true for everyone but not a problem. So nothing happens?

The first night, nothing happens. Because every woman knows 39 other men that are unfaithful. But then it gets complicated.

The real solution, however, is more complicated. The short answer: On the 40th night, something really gory happens. To work it out, check out “Josephine’s problem” at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Induction_puzzles.

At first glance, you’d be struggling to find a solution. Where’s the data? I can’t even guess, because there isn’t enough information! But there is, when you look deeper. It’s a game of chance, you think, because at first, you aren’t able to process all the information properly (and honestly, we aren’t wired to deal with fuzzy probabilities)

Casinos know this - which is why all games that give you the feeling that you can win, have a tiny edge towards them. Even a “high card wins” game can be twisted to: “if the dealer gets a seven, the dealer wins regardless of what you have”. Just doing this, a very slight modification, the game changes in the dealer’s favour.

I even created an online spreadsheet to show you how it works: Go here and see the same game - high card wins - with two scenarios: fair game, or the slight edge to a dealer that the 7 card for him is a winner. The slight edge of the dealer, over 1000 games, always wins.Play long enough, and even a tiny edge will work in your favour.

That’s the other important point. You have to make the edge work, and for that you need to have played very many times. This is where I don’t believe in the Buffett/Munger statement that you should be allowed to only have 10 stocks (their idea of course, is research your positions carefully as if you couldn’t have too many). Buffett himself has had a gazillion positions and his average holding period was 6 months, so it’s not like he practices that himself. (Do what he does, not what he says, is our thinking) The problem with having just 10 positions is that whatever your edge is, will not get to play itself out. Even the best businesses fold (Kodak did, for example) and the worst businesses become great. For a probability to play out, in any field where luck plays a reasonable part: you can’t just play once, you have to be allowed many chances.

It’s altogether difficult to see, over a short term, if a fund manager has beaten an index purely because of luck. In any one year period, or a one-month period, or a one-day period, it’s going to be luck that drives outcomes tremendously. But if there’s really an edge, it will play itself out in the long term, when enough battles have been fought. You don’t need to win them all, just enough to have an edge over the index over time.

If you ask us honestly: what percentage of our performance has been luck? I’m tempted to say “a very large part” because it’s a safe answer. Luck plays a role in all outcomes, and it’s a worse sin to confuse luck as skill than the other way around. The power of luck has a smaller role to play when you play long enough, so our long term goal is to provide better returns over very long periods of time. The skill in this game is to play according to your rules, and a greater skill is to know when to break the rules. It’s been a great year, but it’ll be a long time before we go around taking all the credit for our skill.

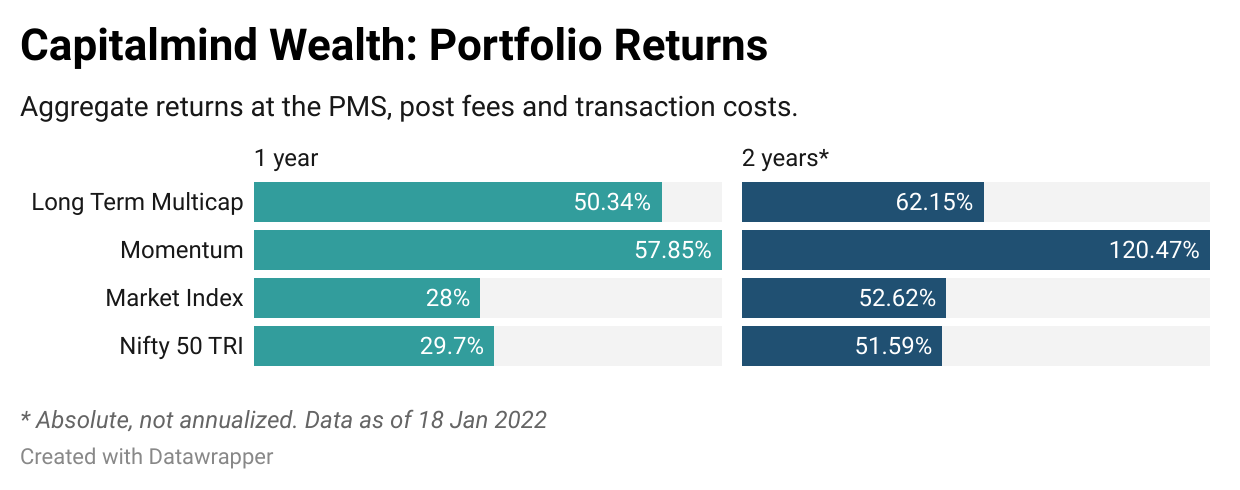

Our focus is to work to build an edge: whether it’s momentum (discipline and rules), market index (just the top market-cap stocks in India+US) or long term multicap (growth and disruption). These edges, we believe, will work over time, but it would be folly to imagine that the last one year - powered partly by the Fed, the ECB and the RBI - is a testament to our skill. It isn’t evident how much skill there is, and our belief is it’s in there, and will take time to unravel. Like the puzzles earlier, what seems like a game of chance will, we hope, prove not to be. We hope to live by the saying: The harder I work, the luckier I get.

It’s going to be fun to meet with all of you on the 22nd, for our biannual town-hall. We will tell you stories about the companies we own, without falling in love with them. We’ll tell you about what we think lies ahead, and the rocky road that gets us there. Please feel free to send in your questions in advance, and we are happy to help in any way we can.

Luckily,

Deepak