When Fear and FOMO collide

The fear of missing out is real, and especially so when the market has given you almost no falls that are deep enough to enter again.

When Fear and FOMO collide

In a discussion about markets at the office, Sir Dev Mallya, whose philosophical talents are often underappreciated, came up with this gem, paraphrasing Mike Tyson:

Everyone has a plan until you’re punched in the teeth with FOMO

FOMO is the Fear of Missing Out. It’s what causes people to believe that if they don’t get in now, the market is going to run away, just like it has in the recent past. It starts off quietly. I will get in, but maybe after a little correction, which is long overdue. And the market refuses to correct, and even the little down days are not too much. At some point, you watch the market hit high after high without much of a retreat. Your friends tell you they’re making so much money. You decide it isn’t going down more - and toss your hat into the ring.

It’s not that you were greedy. You just feared being left out and got in. Peak FOMO happens when markets go up fast and then go up faster. You had a plan - to get in when the market fell 10%, but then, everyone has a plan until….(Sir Dev Mallya’s quote)

In 1929, a celebrated economist, Irving Fisher, said that stocks had reached a “permanently high plateau”. He wasn’t stupid, but the history of the last few years was super bullish: the index had never corrected even 10% since 1926. Even through a recession (shaded below) the index did not fall much. .

You can imagine the frustration of anyone that called a market top - you would be wrong for years and years. The run that started in 1921 went up 6x in 8 years and you could not blame Fisher for thinking any dip was temporary. The FOMO was visible - you simply could not be an outsider.

Subsequently, of course, the index crashed in October 1929, by 11% in a single day. It recovered most of the losses by March 1930 but subsequently, dropped substantially more.

In 1999, the George Soros fund went short internet stocks and lost $600 million (20% of the fund at the time) in six months, as the market flew up like crazy. Then, realizing they were fighting a losing battle, they went in heavy and long, and ended up 34% for the year. In 2000, Stan Druckenmiller, who managed the fund, invested considerably more money into tech stocks, watching the markets go up for two months before the dramatic fall happened. The market fell over 33% in 15 days and the fund ended down 22% in 2000. Druckenmiller resigned.

If such a legendary investor can have FOMO, we are all mere mortals.

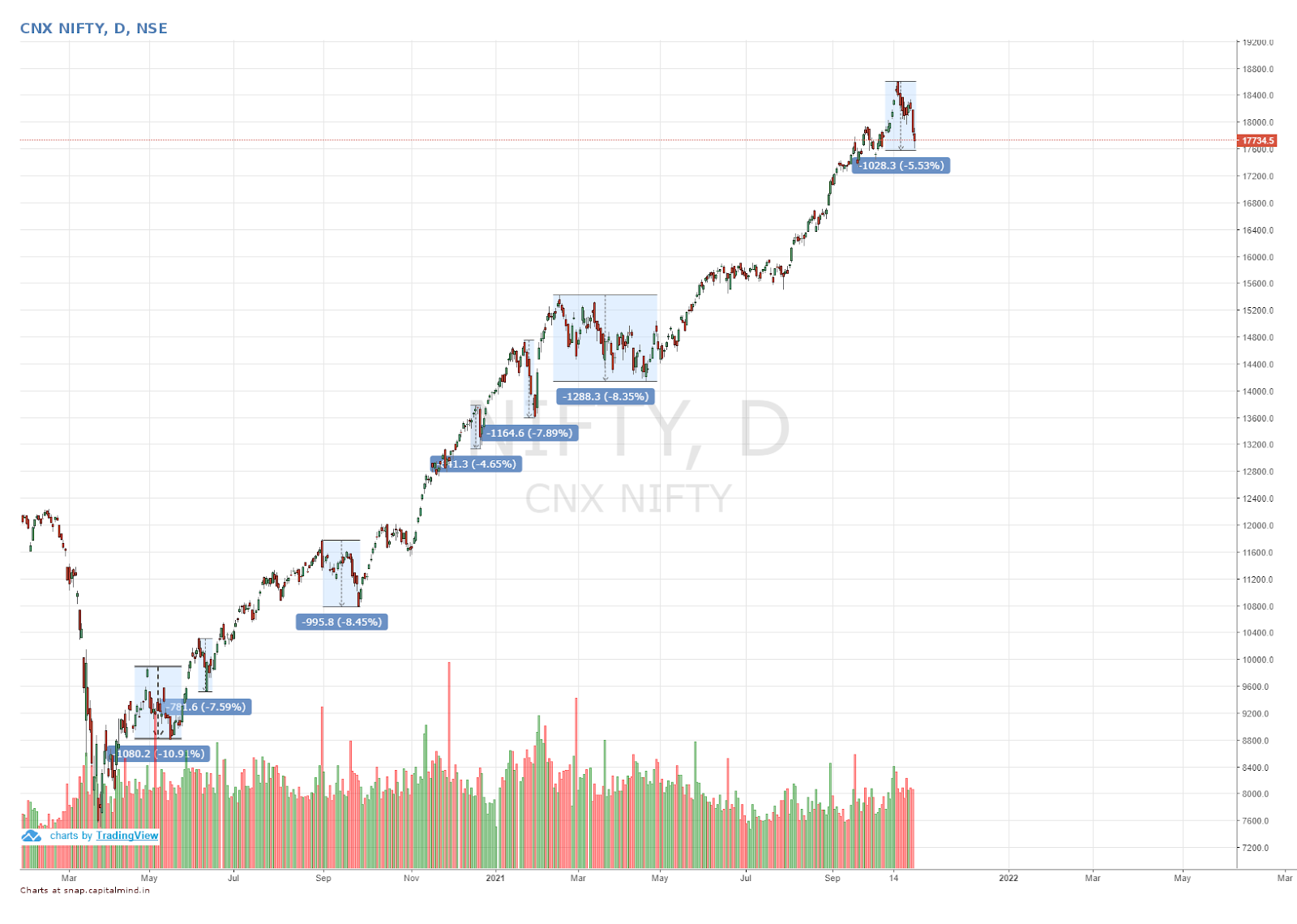

The fear of missing out is real, and especially so when the market has given you almost no falls that are deep enough to enter again. As we speak in October 2021, the market has not seen a 10% decline since May 2020.

But FOMO has lousy consequences. In the market, while the Nifty hasn’t fallen 10%, we have seen stocks down 30% from the top. Even in our own portfolios, some stocks have corrected that much. What happens there? At a portfolio level, both Momentum and Long Term Multicap saw only a 9% fall, even if some stocks corrected 30% or more. It’s the way portfolios work - you will win some and you’ll lose some. But the problem is - we haven’t really lost enough.

What’s wrong with Deepak, you’re thinking. Why does he want the markets to fall? The answer lies in forest fires. In a forest, there’s always flammable material (dried twigs, leaves etc, and of course, wood). The authorities light little fires - “prescribed burns” as they are known in some places - to allow the collected debris to burn when it’s small. The fires don’t get big enough to consume too much, and then more debris comes along and then you do another little fire, and so on.

What happens if you don’t have the little fires? The debris collects. When a spark comes by, from lightning, from a campfire or just about anything, the resulting fire can engulf the forest and take it all out - including civilization that is close by. To avoid the big fires, you need the little fires.

In the markets, the role of a drop is similar. You have little drops so you don’t get the big drops. In every cycle, you get people who are crazy speculators, who borrow to invest and to trade. They benefit from an initial upmove, and that initial profit prompts them to borrow even more to buy stocks - and eventually, when the market falls, they lose their money and then some. Typically such situations happen in small pockets - a few stocks there, that get some enthusiasm and then fall, and the losers don’t impact the overall market that much. But when the markets just keep going up, then everyone starts to “believe”. The market becomes a religion, and everyone’s participating. It won’t fall much, they will think, and voila, it doesn’t fall much. They feel great, and they put more into the market, which goes up even more. This reconfirmation takes you to a point - at some point - where everyone will tell you the coming days will be the grandfather of all bull markets, and that stocks have reached a permanent plateau etc.

Our job is to find that point. We thought we had found it earlier this year - as early as February. Oh, we were so wrong. Luckily, we let our thoughts remain thoughts and didn’t let it impact the portfolios - and continue to believe that’s the correct strategy now too. Let the markets correct meaningfully and we’ll take action. Until such time, we will participate. However, we know that excesses of FOMO too, and we’ll actively try and avoid those.

One excess, recently, was the Squid Game crypto coin scandal, a story that has repeated itself so many times that Xerox is suing it. There’s a successful TV series called Squid Games, and there was a cryptocurrency “coin” with the same name launched recently. The coin was supposed to be a part of an online game where you could play to earn it - instead, the coins could be bought before the launch. The FOMO chasers couldn’t have enough of it - they bought it so heavily that the price went up from 1 cent to $2,800+ in a week. Except for one thing: you couldn’t sell the coin after you’d bought it, because they wouldn’t let you.

That warning should have been enough. It was not. The owners of the cryptocurrency - who control a majority of the total coins issued - then dumped the coin on unsuspecting buyers, taking the price to zero, and leaving themselves seriously enriched. FOMO makes you do strange things and ignore warnings that you simply shouldn’t.

This is evident in the stock market too, sometimes and we’ve learned to recognize most of them. However, this is often confused with “overvaluation” - which, I will argue, exists in nearly every stock today. Paying 90 times earnings for a paint company that grows at 12% a year, or an FMCG giant that makes maida-noodles, baby milk and chocolates - this is also insane. But these are not frauds, so while you could see corrections, they won’t go to zero. And who’s to say 60 times wasn’t already expensive, but they’ve now become 90 times earnings!

In a bull market, you will see FOMO, and even if you let your investments lie, and plan to sell on a correction rather than when the stock is going up, you will do well. As fund managers, we are expected to be soothsayers, knowing every gyration of the market. We don’t. No one does. At best, we are people that react to the market’s gyrations and identify opportunities that could benefit from the next gyration. We are conditioned to believe that market prices are nothing, earnings are everything. In reality, earnings are a slave to market prices as well - you will find that after market prices fall, certain companies that were showing great earnings growth start slowing down for no apparent reason. Even marquee names. Yes Bank was one such, as were DHFL and a few others.

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do sir?”, said Paul Samuelson, an economist. He’d written that 5% inflation was tolerable, then 3% and then 2% - until a newspaper article asked him to make up his mind. That was his response. And indeed, changing our mind is not a bad thing at all - even though we live in an age that holds people’s twitter and facebook accounts hostage because of something they said 25 years ago. You’re allowed to be a different person today, and every single day, and that freedom is the essence of life itself.

Being reactive and embracing change, even in a FOMO environment, is a good way to behave. It’s also less stressful, because every prediction comes with a score card: right or wrong, and being wrong is stressful.

The book: Moneywise!

I have a new book on the markets. The very basics of investing, for a relative beginner in the financial world. It’s called “Moneywise” and I will have signed copies for you by the end of December. (India only for the moment, but it will be available on Kindle as well. If you want a link to pass on: https://amzn.to/3CgkGea ) It starts with the words I wrote in a letter to you, a few months back.

An excerpt from another part of the book:

Do not underestimate the value of luck

The reality is, you have no idea how the market will like your

stock. It may own a goose that lays golden eggs and yet, the

stock price doesn’t go up. The fact that you chose a stock after

a lot of work, or that the business itself has performed, means

nothing. It takes a bit of luck for the market to discover it too.

For many years, sometimes even a decade, a great stock might

have languished, testing your patience. You need that little bit of

luck; otherwise it doesn’t work.

To maximize the impact of luck, you’re going to have to

diversify and take on multiple bets. That way, if luck shines on a

few, that’s enough to give you great returns. In fact, you have to

work really hard to be able to get lucky.

When opportunity knocks, you gotta open the darn door,

not just sit around! So yeah, the people who work hard succeed

because they take the luck when it comes and make it work

for them. That is not unimportant. Don’t take away the wrong

meaning that if it’s all going to be about luck anyway, let me

sit and do yoga while I wait for luck to drop money into my

bank account.

But don’t attribute your success to skill. You are incredibly

lucky if you’re part of the top 5 percent of India, the people

who get to invest in stocks. You’re incredibly lucky to have lived

through an era when the world’s central banks ensured you could

buy stocks and not lose money. And when you do make money,

it’s probably due to a lot of the factors you don’t control, which

work in your favour anyhow and make your success happen.

Over the years, I’ve learnt one thing. The more you share, the more you receive. It’s not always simultaneous, but the world finds a way to eventually even the score. So in the delightful time that is Diwali, I hope you are able to share your happiness, joy and wealth with the people around you, and that you enjoy a life of prosperity ahead!

FOMO-estively,

Deepak